What Is Poetry? |Types, Poetic Devices & Examples

Poetry is a form of writing that uses carefully chosen words, rhythm, and sound to express emotions and ideas in a condensed, artistic way. From structured forms like sonnets to flowing free verse, poets use various techniques to create works that resonate deeply with readers.

Key features of poetry

What makes poetry different from other forms of writing, especially prose, is its focus on compressing meaning and emphasizing the musical qualities of language. Poets arrange words not just to tell stories but to create vivid images and evoke emotions with fewer words.

Sound plays a crucial role in poetry. Rhythm, rhyme, and other sound patterns help give poems a musical flow that can move us emotionally in ways that plain language often can’t. These musical features also have deep historical roots: before writing existed, rhythm and rhyme served as memory aids, making it easier to remember and share stories orally.

Poetry relies on several key elements:

- Structure: How a poem is arranged on the page, using lines, stanzas, and forms such as sonnets or haikus.

- Sound devices: Rhythm, rhyme, alliteration, assonance, and consonance that shape how the poem sounds.

- Figurative language: Tools like metaphor, simile, personification, symbolism, and imagery that add depth and vividness.

- Diction: The careful choice of words that affects tone and meaning.

- Tone and mood: Τhe writer’s attitude and the emotional atmosphere experienced by the readers.

- Theme: The underlying message or idea the poem explores.

Together, these elements allow poets to capture human experience with great economy and turn it into something artistic and resonant.

- “Write a poem about loss in a hopeful tone.”

- “Write a nature poem that feels playful.”

- “Write a poem in the voice of an old sea captain.”

Compare the outputs and ask:

- How does diction shift?

- What imagery does each take use?

- How do sound devices (like alliteration or assonance) differ?

This strengthens your understanding of tone, mood, and voice.

Common types of poetry

Poetry is a rich and varied art form with many different types, often grouped by how they’re structured or how they’re created. Some follow set patterns and rules—like sonnets, haikus, and odes—while others break free from traditional forms, such as free verse or prose poems. There are also poems defined by how they’re made or performed. For example, found poems are created by reshaping existing texts, while slam poetry is meant to be performed aloud with energy and emotion. Here’s a look at some common types across these categories:

Classic and formal poetry

Classic and formal poetry follows established structures, such as fixed line counts, rhyme schemes, or syllable patterns. These forms often originate from long literary traditions, emphasizing balance, rhythm, and careful control of language.

- Haiku: A three-line Japanese poem with a 5-7-5 syllable pattern, traditionally capturing a moment in nature. For example, Matsuo Bashō’s famous haiku about a frog jumping into a pond.

- Sonnet: A 14-line poem with various rhyme schemes (such as Shakespearean or Petrarchan), often exploring themes of love, beauty, or mortality. Shakespeare’s “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” is one of the most famous examples.

- Ode: A formal poem expressing praise or celebration, often with an elevated tone. Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale” and Neruda’s “Ode to My Socks” show the range from serious to playful.

- Elegy: A reflective poem mourning loss or death, such as Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” or W.H. Auden’s “Funeral Blues.”

- Limerick: A humorous five-line poem with a bouncy AABBA rhyme scheme, often playful or nonsensical in tone.

- Cinquain: A five-line poem with a set syllable count, often focusing on vivid imagery.

- Lyric poem: A personal and emotional poem, often musical in nature, which can follow formal or free forms, like many of Emily Dickinson’s short, introspective poems.

Free and experimental poetry

Free and experimental poetry breaks away from traditional rules, prioritizing expression, visual form, or creative process over fixed patterns of rhyme and meter

- Free verse: Poetry without fixed rhyme or meter, relying on the natural rhythm of speech and line breaks for emphasis. Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” pioneered this form in American poetry.

- Prose poem: Written in paragraph form like prose but using poetic techniques such as imagery and rhythm.

- Found poem: Made by rearranging words from non-poetic texts, like product labels, newspaper articles, or instruction manuals, much like a collage that forms a new poem from old pieces.

- Blackout poetry (or erasure poetry): Created by blacking out words from existing texts, such as old books, newspapers, or magazines, leaving selected words visible to form a new poem. Austin Kleon’s “Newspaper Blackout” series popularized this form across the internet.

- Concrete poem: A poem whose visual arrangement on the page reflects its subject. For instance, a poem about rain might be shaped like falling raindrops.

Narrative and constrained forms

Some types of poetry are defined less by fixed patterns and more by what the poem does or

the constraints it follows. These approaches often overlap with both formal and free verse.

- Narrative poem: A poem that tells a story through verse, using elements like plot, characters, and setting. Narrative poems can be highly structured (such as ballads and epics) or written in looser forms, including free verse.

- Acrostic: A poem built around a constraint in which the first letters of each line spell out a word or message. Acrostics can appear in both formal and informal styles and are often used as a creative exercise or to embed hidden meanings.

These categories aren’t set in stone. Many poems blend features from different types, and poets often experiment beyond traditional boundaries. A poem might tell a story in free verse, for example, or use the structure of a haiku to describe urban life rather than nature.

Consider these questions to guide your exploration:

- How does the structure change between each type? (line count, syllable patterns, rhyme scheme?)

- How does the rhythm or pacing differ across the poem types?

- What mood or tone does each form create with the same subject?

- How does the choice of words shift to fit each style?

This exercise helps deepen your understanding of poetic forms and how structure shapes meaning.

Essential poetic devices

Poetic devices help transform ordinary language into something more vivid, musical, or thought-provoking. These techniques are sometimes called literary devices when they appear across all forms of writing. Some devices focus on sound—like rhyme and rhythm—while others work with meaning, such as metaphor and symbolism.

Understanding these devices can deepen your appreciation of poetry and help you recognize the craft behind the words.

Here are some of the most common and powerful poetic devices:

Sound devices

These techniques focus on how a poem sounds, using patterns and repetitions to create rhythm, melody, and emphasis.

- Rhyme: The repetition of similar sounds, usually at the end of lines. Rhyme can create a sense of harmony and make poems more memorable—like the AABB pattern in many nursery rhymes.

- Alliteration: The repetition of the same consonant sound at the beginning of nearby words, such as “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers.” It creates a musical quality and can emphasize certain words.

- Assonance: The repetition of vowel sounds within words, like the long “o” sound in “slow road home.” It’s subtler than rhyme but adds a melodic quality to lines.

- Onomatopoeia: Words that sound like what they describe, such as “buzz,” “crash,” or “whisper.” Onomatopoeias bring sounds directly into the poem, making descriptions more immediate and sensory.

- Rhythm and meter: The pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables that creates the “beat” of a poem. Iambic pentameter (da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM) is one of the most common meters in English poetry.

Figurative language and imagery

These devices help poems move beyond literal meaning by using comparisons and vivid descriptions that engage the reader’s imagination and feelings.

- Metaphor: A comparison that says one thing is another thing, creating a new way of seeing. When Shakespeare writes “All the world’s a stage,” he’s not being literal—he’s revealing something about how life works.

- Simile: A comparison using “like” or “as,” such as “Her smile was like sunshine” or “Strong as an ox.” Similes are more explicit than metaphors but serve a similar purpose.

- Personification: Giving human qualities to non-human things, like “the wind whispered through the trees” or “time marches on.” This device helps readers connect emotionally with abstract concepts or nature.

- Imagery: Vivid descriptive language that appeals to the senses—sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell. Good imagery helps readers experience what the poem describes rather than just reading about it.

- Symbolism: When an object, person, or action represents something beyond its literal meaning. A rose might symbolize love, a storm might represent inner turmoil, or a journey might stand for personal growth.

Structural devices

These tools shape the poem’s form and flow, controlling how it looks and how readers move through it.

- Repetition: Repeating words, phrases, or structures for emphasis or rhythm. In Poe’s “The Raven,” the repeated “Nevermore” becomes increasingly haunting with each use.

- Enjambment: When a sentence or phrase runs over from one line to the next without punctuation, creating a sense of flow or urgency. Enjambment is the opposite of stopping at the end of each line.

- Caesura: A deliberate pause or break within a line of poetry, often marked by punctuation. Caesura can create dramatic emphasis or give readers a moment to absorb what they’ve read.

Poets rarely use just one device at a time. Instead, they layer multiple techniques to create rich, complex effects. As you read more poetry, you’ll start noticing how these devices combine to shape the poem’s overall impact.

How poetry works: Bringing it all together

Poetry works by combining all the elements we’ve explored, like form, sound, imagery, and meaning, into a unified whole that’s greater than the sum of its parts. When you read a poem, you’re doing more than just processing words on a page; you’re experiencing how the poet weaves together structure, devices, and carefully chosen language to create something that resonates on multiple levels at once.

Take Emily Dickinson’s famous opening stanza as an example:

Hope is the thing with feathers —

That perches in the soul —

And sings the tune without the words —

And never stops — at all —

This brief stanza layers multiple devices. The extended metaphor compares hope to a bird, making an abstract feeling concrete and vivid. The imagery appeals to our senses—we can picture a small bird perched inside us, hear its wordless song. Dickinson’s characteristic em dashes create caesuras that control our reading pace, making us pause and linger on key moments like “never stops — at all —.” The simple language and gentle rhythm reinforce the poem’s comforting message about hope’s persistence.

Form, sound, and meaning work together here to create something more powerful than any single element could.

Examples: Classic poems to explore

Reading poetry is one thing, but unpacking how the elements we’ve discussed come together in actual poems can deepen your understanding. Here are two classic poems that demonstrate different styles and techniques, both accessible to readers new to poetry.

One of the most famous American poems, “The Road Not Taken,” tells the story of a traveler choosing between two paths in a wood. Written in 1916, it’s often read as a reflection on life choices and their consequences. Here are the first and last stanzas:

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

(…)

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

What to notice: This poem uses metaphor on multiple levels—the literal roads become symbols for life choices. Its ABAAB rhyme scheme, where the first, third, and fourth lines rhyme and the second and fifth lines rhyme, gives the poem structure without feeling rigid. Frost’s simple, conversational language explores profound themes, while the final stanza’s famous lines use repetition (“Two roads diverged”) and a dramatic pause (“and I—”) to create emphasis. It’s also a strong example of narrative poetry, telling a complete story that includes personal reflection.

Also known as “Daffodils,” this 1807 poem captures a moment when Wordsworth encountered a field of daffodils during a walk. It’s a celebrated example of Romantic poetry, emphasizing nature’s power to uplift the human spirit. Below is the first stanza:

That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

What to notice: Wordsworth fills this poem with vivid imagery that appeals to multiple senses—we see the “golden daffodils,” feel the “breeze,” and almost hear them “fluttering and dancing.” The poem uses simile (“lonely as a cloud”) and personification (daffodils “dancing”) to bring the scene to life. Notice the strong ABABCC rhyme scheme and how the rhythm mimics the gentle movement of flowers in the wind. This poem is a great example of how poets capture fleeting moments and transform them into lasting emotional experiences.

Recommended poems for beginners: A reading list

If you’re new to poetry and want to explore different styles and voices, this curated list is a great starting point. These thirteen poems range from classic formal works to modern free verse, giving you a sense of poetry’s range and evolution. Start with whichever titles intrigue you—there’s no wrong order—and notice how each poem uses language, sound, and structure differently.

Classic and formal poetry

- “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” (Sonnet 18) by William Shakespeare— Perhaps the most famous sonnet in English, demonstrating how formal structure can intensify emotion and meaning.

- “The Road Not Taken” by Robert Frost—An accessible narrative poem about choice and consequence, showing how metaphor works through an entire piece.

- “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” by Dylan Thomas—A powerful villanelle (a form with repeated lines) about facing death with defiance and passion.

- “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” by William Wordsworth—A Romantic poem celebrating nature’s ability to lift the human spirit, filled with vivid imagery.

- “The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe—A longer narrative poem with haunting repetition and musical rhythm that builds atmosphere and dread.

- “Because I could not stop for Death” by Emily Dickinson—A meditation on mortality using simple language and Dickinson’s characteristic dashes to create pauses.

Free verse and experimental poetry

- “The Red Wheelbarrow” by William Carlos Williams—An incredibly short imagist poem proving that profound moments can be captured in just a few words.

- “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou—A powerful poem of resilience and strength, using repetition and rhythm to build emotional force.

- “Harlem” by Langston Hughes—A brief but impactful poem asking what happens to dreams deferred, using vivid similes.

- “Wild Geese” by Mary Oliver—A comforting free verse poem about belonging and self-acceptance.

- “Mirror” by Sylvia Plath—A confessional poem using personification to explore themes of aging, identity, and self-perception with stark honesty.

- “Introduction to Poetry” by Billy Collins—A funny, accessible poem about how to read poetry without overanalyzing it, perfect for beginners feeling intimidated.

- “anyone lived in a pretty how town” by e.e. cummings—An experimental poem playing with grammar, capitalization, and word order to tell a love story in an entirely unique way.

Frequently asked questions about what is poetry

- What is a line break in a poem?

-

A line break in poetry is the point where one line ends and the next begins. Unlike prose, where sentences flow continuously, line breaks in poetry help shape rhythm, pace, and meaning. They create pauses, emphasize words or ideas, and affect how you experience the poem’s sound and structure.

Here’s a snippet from Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”:

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.Each line break encourages a slight pause, guiding the poem’s gentle rhythm and highlighting important phrases.

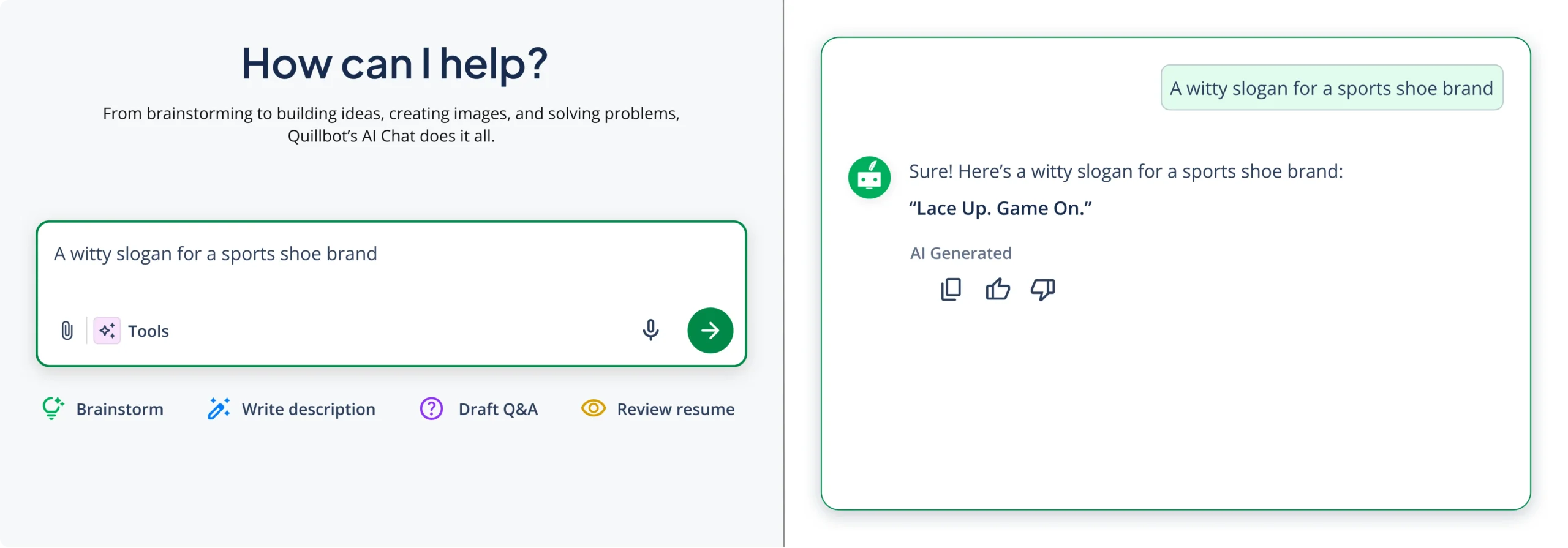

Curious about more poetry terms or techniques? Ask QuillBot’s AI Chat for quick, clear explanations anytime.

- What is a refrain in poetry?

-

A refrain in poetry is a line or group of lines repeated at regular intervals, often at the end of stanzas. This repetition adds rhythm and emphasis, helping to reinforce the poem’s mood or central theme.

For example, in Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven,” the repeated word “Nevermore” creates a haunting, melancholic mood and underscores the finality of death—the idea that what’s lost is gone forever and will never return.

Want to explore more about poetic terms like refrains? Ask QuillBot’s AI Chat for clear explanations or examples.

- What is a foot in poetry?

-

A foot in poetry is the basic unit of rhythm, made up of a set pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables. It’s like a small “beat” that helps create the poem’s overall meter and flow.

For example, the most common foot in English poetry is the iamb, which has an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed one, as in the word “be-LIEVE.”

Do you have questions about poems, styles, or literary devices? Let QuillBot’s AI Chat guide you through the world of poetry with ease.

- What is the difference between poetry and prose?

-

The main difference between poetry and prose lies in how language is arranged and what it emphasizes.

- Prose is the everyday form of written language—organized into sentences and paragraphs, like novels, essays, or articles. It flows continuously and focuses mainly on clear storytelling or conveying information.

- Poetry, by contrast, is arranged in lines and often stanzas, with careful attention to sound, rhythm, and condensed meaning.

While prose prioritizes clarity and narrative flow, poetry emphasizes the musical qualities of language and packs more meaning into fewer words.

Curious about poetry? Ask QuillBot’s AI Chat for explanations, examples, or tips

Cite this QuillBot article

We encourage the use of reliable sources in all types of writing. You can copy and paste the citation or click the "Cite this article" button to automatically add it to our free Citation Generator.

Nikolopoulou, K. (2026, March 08). What Is Poetry? |Types, Poetic Devices & Examples. Quillbot. Retrieved March 9, 2026, from https://quillbot.com/blog/creative-writing/what-is-poetry/